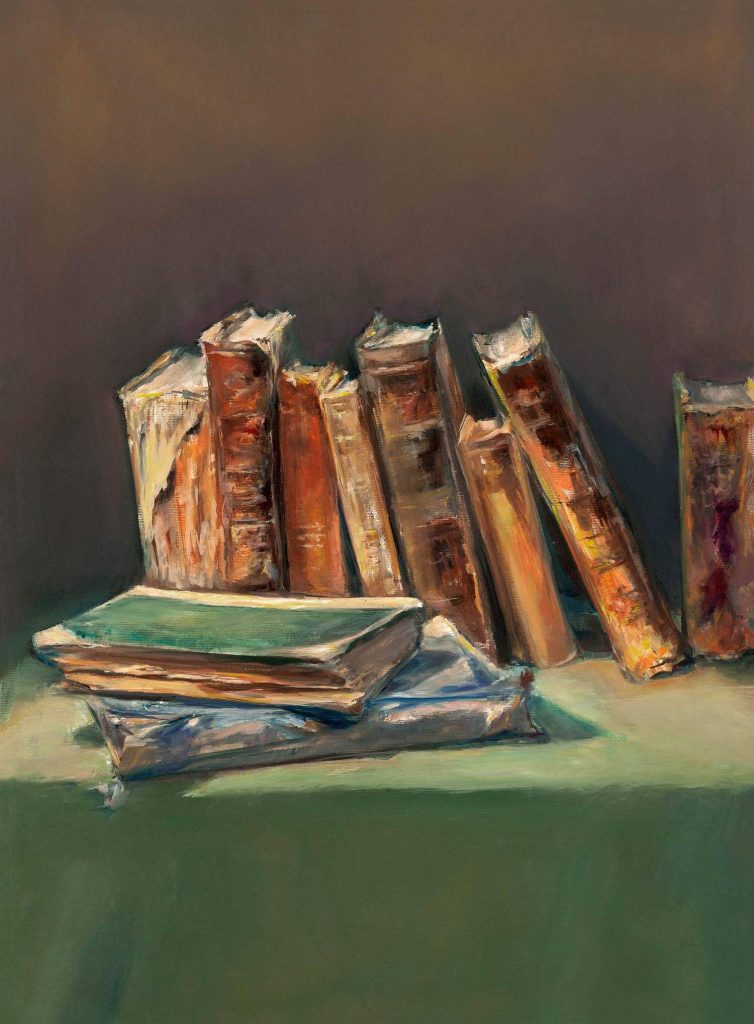

This painting is dedicated to my grandfather, ‘Mori’ Moshe Giat, who passed away 10 years ago at the age of 98.

I remember him in his modest Jerusalem apartment, holding a carved bamboo writing utensil, pen nib, ink and a parchment. Books and scrolls surrounded his seat. His eyes rose only when a guest visits.

My grandfather was a rabbi and the head of a community in the Katamonim, a Jerusalem neighborhood. His community honored him with a name ‘Mori (teacher) Moshe’.

I remember him in his modest Jerusalem apartment, holding a carved bamboo writing utensil, pen nib, ink and a parchment. Books and scrolls surrounded his seat. His eyes rose only when a guest visits.

My grandfather was a rabbi and the head of a community in the Katamonim, a Jerusalem neighborhood. His community honored him with a name ‘Mori (teacher) Moshe’.

Mori Moshe was born in the city of Sanaa in Yemen, a descendant of a family of spiritual leaders in an ancient Jewish community. In Yemen, among other things, he made a living from writing religious articles, making jewelry and small-scale trade, but devoted most of his time to studying Torah and Halacha.

In the absence of printing, books were scarce. Therefore, whenever a Jewish cogitation book came by, the people would sit down and copy it by handwriting. These were writings of Halacha that dealt with all aspects of life in the spirit of the Torah, and the Jews studied them and lived by them for centuries. Over the generations, footnotes have also been written in the books by the teachers. A page in the book was constructed from layers in time: an ancient manuscript of Halacha and interpretations and around it written footnotes passed between generations by a teacher and his son. My grandfather had ancient books that contained additions in footnotes by his grandfather, his father Mori Yihye, and his own.

In the absence of printing, books were scarce. Therefore, whenever a Jewish cogitation book came by, the people would sit down and copy it by handwriting. These were writings of Halacha that dealt with all aspects of life in the spirit of the Torah, and the Jews studied them and lived by them for centuries. Over the generations, footnotes have also been written in the books by the teachers. A page in the book was constructed from layers in time: an ancient manuscript of Halacha and interpretations and around it written footnotes passed between generations by a teacher and his son. My grandfather had ancient books that contained additions in footnotes by his grandfather, his father Mori Yihye, and his own.

Immigrating to the homeland of Israel has been the dream of Jews throughout time. The finale of every Jewish prayer, over 2000 years at everywhere diaspora, has actually been a vocal dream: “Next year in Jerusalem”.

It only grew stronger in Islamic countries, considering the suffering inflicted by the local residents.

With the establishment of Israel, the Zionist leadership reached an agreement with the Yemeni ruler on the immediate possibility of bringing the Jews to Israel. Having no choice, the Jews sold their property at a very low price or even had to simply abandon it.

While prioritizing his other properties, my grandfather made NONE of it when it came to his books. He carried them, always, close to his chest – very tight indeed.

He protected them also in the harsh desert conditions on the way to the transit camp in the city of Eden, whereby entire families made on foot and some on donkeys. On their tough marching way, robbers attacked the weak and sick among them. Many people died, the belongings dwindled, but my grandfather kept protecting the books.

In the transit camp in Eden, which was designed for thousands but populated tens of thousands, conditions were unbearable and diseases broke out. The Zionist leadership urgently flew the immigrants to Israel for months in a row, even on Yom Kippur. The plane seats were removed in order to crowd the passengers. Flights were expensive for the young country and passengers were asked to donate from their meager possessions. My family members did the same, but my grandfather protected the books from all harm. When the impoverished immigrants arrived to Israel, merchants offered financial temptations in exchange for the ancient books, but Mori Moshe was never tempted.

It only grew stronger in Islamic countries, considering the suffering inflicted by the local residents.

With the establishment of Israel, the Zionist leadership reached an agreement with the Yemeni ruler on the immediate possibility of bringing the Jews to Israel. Having no choice, the Jews sold their property at a very low price or even had to simply abandon it.

While prioritizing his other properties, my grandfather made NONE of it when it came to his books. He carried them, always, close to his chest – very tight indeed.

He protected them also in the harsh desert conditions on the way to the transit camp in the city of Eden, whereby entire families made on foot and some on donkeys. On their tough marching way, robbers attacked the weak and sick among them. Many people died, the belongings dwindled, but my grandfather kept protecting the books.

In the transit camp in Eden, which was designed for thousands but populated tens of thousands, conditions were unbearable and diseases broke out. The Zionist leadership urgently flew the immigrants to Israel for months in a row, even on Yom Kippur. The plane seats were removed in order to crowd the passengers. Flights were expensive for the young country and passengers were asked to donate from their meager possessions. My family members did the same, but my grandfather protected the books from all harm. When the impoverished immigrants arrived to Israel, merchants offered financial temptations in exchange for the ancient books, but Mori Moshe was never tempted.

In the last years of his life, my grandfather was confined to his bed. I visited him often with my mother, and got closer to his world. After his death, we perused his books and discovered many things. Among others, the date of his birth and his full name given to him at birth, documented in a footnote written by his father in one of the pages.

People tell me they feel that this painting was born more from the heart than from the hand. Maybe it’s true. For me, this is a personal touch through home to the concept of the ‘People of the Book’, the nickname of the Jewish people.

It is said that biblical scriptures were passed on by word of mouth.What’s important is that they were passed through drawings on pottery, papyruses, parchment scrolls, and writings as the ones that my grandfather kept.

It is said that biblical scriptures were passed on by word of mouth.What’s important is that they were passed through drawings on pottery, papyruses, parchment scrolls, and writings as the ones that my grandfather kept.

I called the painting ‘At the Heder’ because that is the name in Jewish communities for a place where children study the Torah.

In honor of my grandfather, Mori Moshe Tsahalon Giat of blessed memory

Special thanks to Hovav, Yifat and Yaron Talpaz for writing this text with me.

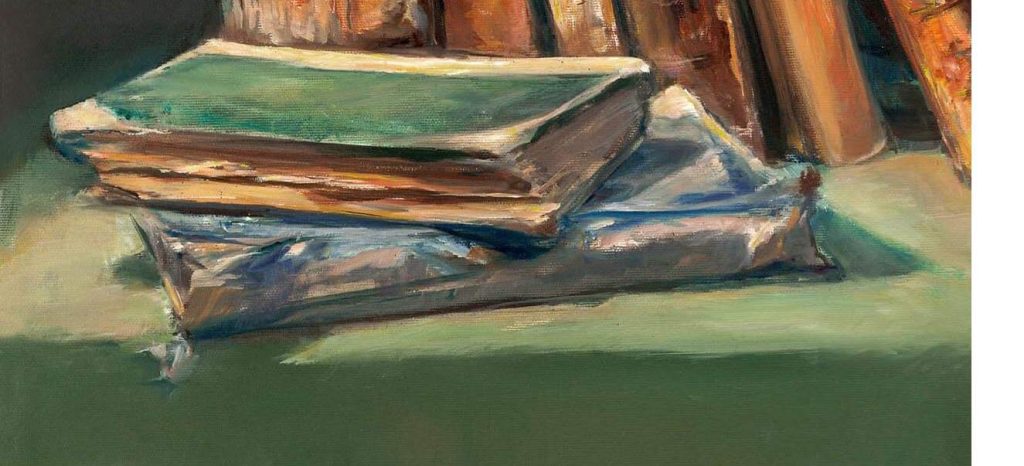

At the ‘Heder’, Adi Tsimhoni, 50X70 cm, detail